Before you even think about casting off, the most important piece of safety gear you have is a solid understanding of the boating rules of the road. These aren't just helpful suggestions—they're the law. Think of them as the traffic rules for every waterway, from a quiet lake to the open ocean.

Why the Rules of the Road Are Your Best First Mate

Operating a boat is a lot like driving a car in one key way: you’re sharing the space with others. The rules of the road give every boater a shared, universal language to follow, which is absolutely essential for avoiding dangerous close calls and collisions. Mastering these rules isn't just a good idea; it's the bedrock of good seamanship and a captain's number one responsibility.

The whole system boils down to right-of-way. The rules clearly spell out which boat is the "stand-on" vessel (the one that maintains its course and speed) and which is the "give-way" vessel (the one that needs to take action to stay clear). This system eliminates confusion and prevents the kind of chaos you'd otherwise see in a busy channel.

The Foundation of Modern Navigation

The rules we follow today are anything but new. They’re built on a framework that has been tested and refined for well over a century to keep mariners safe worldwide. The International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, better known as the COLREGs, have been the gold standard for more than 125 years. First adopted way back in 1897, they created a uniform set of directives that are just as critical now as they were then. You can dive deeper into the fascinating history of these maritime rules on USNI.org.

The real goal behind all these regulations is predictability. When you know what the other boater is supposed to do, you can make smarter, safer decisions. It’s that simple.

Understanding the Pecking Order

On the water, not all boats are created equal, especially when it comes to their ability to maneuver. The rules of the road establish a clear hierarchy—a "pecking order," if you will—that dictates which vessels have priority over others. This is mostly based on which vessel is less nimble and has a harder time getting out of the way.

For example, a massive cargo ship can't just slam on the brakes or make a sharp turn, so smaller, more agile recreational boats have a duty to stay well clear of it. In the same way, a sailboat relying on wind has less control over its movement than a powerboat that can turn on a dime.

This hierarchy is something every boater needs to have memorized. It's the key to knowing your responsibility in almost any situation you'll encounter.

Quick Guide to Vessel Pecking Order

This table breaks down which vessels generally get to hold their course and which ones need to yield. The vessel on the left has priority over the vessel on the right.

| Vessel Type (More Privileged) | Vessel Type (Less Privileged) |

|---|---|

| Vessel Not Under Command (e.g., engine failure) | A Vessel Restricted in its Ability to Maneuver |

| Vessel Restricted in Ability to Maneuver | A Vessel Engaged in Fishing |

| Vessel Engaged in Fishing | A Sailing Vessel |

| Sailing Vessel (under sail) | A Power-Driven Vessel |

| Power-Driven Vessel | A Seaplane |

Knowing this pecking order by heart is non-negotiable. It tells you exactly how to react when you meet another boat, ensuring you do the right thing to keep everyone safe.

Understanding Stand-On vs. Give-Way Vessels

When two boats find themselves on a potential collision course, the boating "rules of the road" are designed to take the guesswork out of the equation. They do this by assigning clear roles to each vessel. Understanding the critical difference between being the stand-on vessel and the give-way vessel isn't just a good idea—it's the foundation of preventing accidents on the water.

Think of it like approaching a four-way stop on a country road. There’s a clear system for who goes first to keep things orderly and safe. On the water, these roles create a predictable framework so every skipper knows what to expect from the other. The goal isn't about being "right," it's about everyone getting home safely.

Knowing your role in any given encounter allows you to take clear, decisive action that other boaters will immediately understand.

The Role of the Stand-On Vessel

If your boat is the stand-on vessel, you have the right-of-way. Your most important job is to be predictable. That means you must maintain your course and speed. By holding steady, you make it easy for the other boat to anticipate your path and maneuver around you.

But this isn't a free pass to zone out. As the stand-on vessel, you still have a crucial responsibility under Rule 5 (the "look-out rule") to pay close attention. If the other boat—the give-way vessel—isn't taking action to avoid you and a collision seems possible, the responsibility shifts.

The stand-on vessel is required to take action to avoid a collision if it becomes apparent that the give-way vessel is not taking appropriate action. Safety always overrides the right-of-way.

This is a point I can't stress enough. You never, ever just plow ahead into a dangerous situation insisting you have the right-of-way. If an accident is about to happen, you must do whatever it takes to avoid it.

The Responsibility of the Give-Way Vessel

As the operator of the give-way vessel, your duty is straightforward: you must take early and substantial action to keep well clear of the stand-on vessel. You are the one who has to yield. The burden of action is completely on you.

Your maneuvers need to be obvious and made with plenty of time to spare. A tiny, last-second turn can create confusion, while a bold, early course change clearly signals your intentions. Remember, boats don't have brakes and seat belts like cars do. Slowing down means altering course or reversing your engines. To keep everyone safe, the official Rules of the Road lay out specific actions for every scenario—overtaking, meeting head-on, and crossing paths.

Here’s what’s expected of a give-way vessel:

- Act Early: Don't wait until things get tight. As soon as you see a potential conflict, start your maneuver.

- Act Substantially: Make your change in course or speed big enough for the other skipper to easily see and understand. No subtle moves.

- Pass at a Safe Distance: Give the other vessel a wide berth. Never cut it close.

- Avoid Crossing Ahead: The safest and most common practice is to alter your course to pass behind the stern of the stand-on vessel.

Mastering these concepts is a huge part of being a responsible skipper. For a more detailed look at how these roles apply in specific situations, you can dive into our ultimate guide to navigation rules. This proactive, safety-first mindset is what separates a true boater from a hazard on the water.

Making Sense of On-Water Encounters

Out on the water, the "rules of the road" are just as important as the ones we follow in our cars. Knowing how to handle the most common boat-to-boat situations isn't just about following regulations; it’s about swapping panic for confident, predictable action. When you and another boat are on a potential collision course, the rules clearly define who has the right-of-way based on how you're approaching each other.

There are really only three main scenarios you'll run into: meeting another boat head-on, crossing paths, or overtaking. Let's break down each one.

The Head-On Situation

Think about walking down a narrow hallway. When someone approaches from the other direction, you both instinctively move to your right to avoid bumping into each other. It’s the exact same principle for two powerboats meeting head-on.

When two power-driven vessels are on a direct or nearly-direct collision course, each captain must alter course to starboard (to the right). This simple maneuver ensures you'll pass each other port-to-port, or left-side to left-side. It’s a universal rule that removes all the guesswork.

The Crossing Situation

This is probably the most frequent encounter you'll have, and it's critical to get it right. A crossing situation happens anytime two powerboats are approaching at an angle, and it’s not a head-on meeting or one boat passing another. Imagine a four-way intersection on the road, but without any stop signs.

The rule is actually quite simple:

- If a boat is approaching from your starboard (right) side, they have the right-of-way. They are the "stand-on" vessel.

- You are the "give-way" vessel. It's your job to take early and obvious action to stay clear, which usually means slowing down and steering to pass safely behind them.

A great way to remember this, especially at night, is the phrase: "If to your starboard red appear, it is your duty to keep clear." A boat's port (left) side is marked with a red navigation light. Seeing that red light crossing from your right means you have to give way.

On the flip side, if you see a boat approaching from your port (left) side, you are the stand-on vessel. Your job is to maintain your course and speed. If you see their green starboard light, it's a clear signal that you have the right to proceed, but always keep a close watch to make sure they follow the rules.

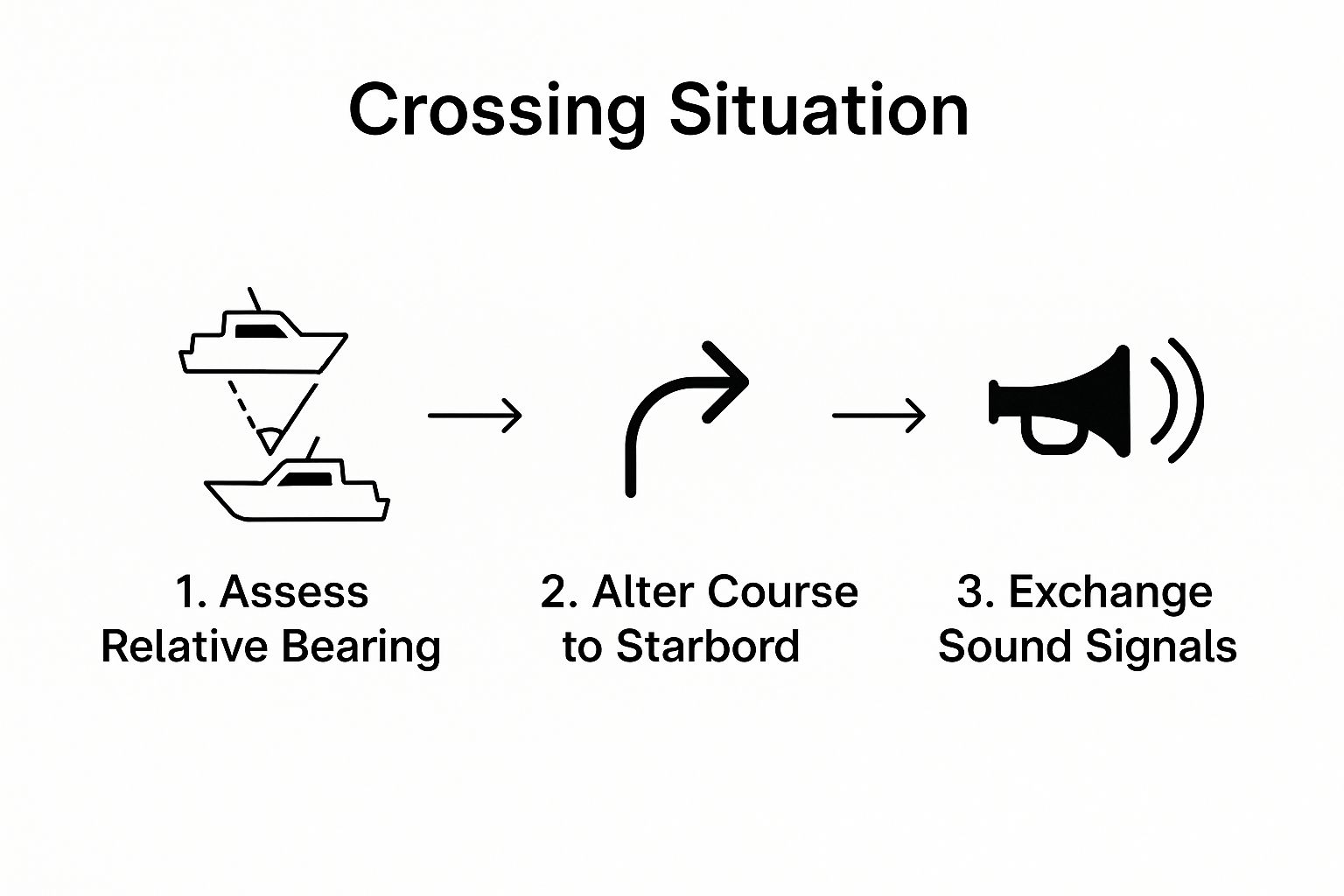

This infographic lays out the decision-making process for handling a crossing situation safely.

As you can see, safe boating comes down to a constant loop of observing what's around you, making a clear decision, and acting in a way that everyone understands.

The Overtaking Situation

When you come up from behind another boat to pass it, you are the overtaking vessel. This automatically makes you the give-way vessel, and it doesn't matter what kind of boat you're in. The boat being passed is always the stand-on vessel.

Your responsibility is to keep well clear of the boat you're passing. You can choose to pass on either their port (left) or starboard (right) side, but you need to make your move obvious and leave plenty of space. The boat being overtaken simply needs to hold its course and speed.

So, when are you officially "overtaking"? The rule defines it as approaching another vessel from any direction more than 22.5 degrees abaft its beam. To put it simply, if you're approaching from an angle where you'd only be able to see the other boat's white sternlight at night, you are overtaking.

In every one of these scenarios, predictability is the key to safety. According to U.S. Coast Guard reports, a shocking 75% of boating fatalities happened on boats where the operator had no safety instruction. Knowing these rules is the first, most important step you can take to be a safer boater and avoid becoming a statistic. Always remember, even when you are the stand-on vessel, your ultimate duty is to do whatever it takes to avoid a collision.

Reading Lights And Shapes Like A Seasoned Captain

Once the sun goes down or the fog rolls in, the water starts communicating in a language of its own. This language, spoken through a specific system of lights and shapes, is one of the most critical skills any boater can master. It's how you'll figure out what another vessel is doing, where it's headed, and what kind of boat it is, all from a safe distance.

Think of navigation lights as the traffic signals of the sea. They're a universal code that cuts through the confusion and guesswork of nighttime encounters. Getting them down cold is a non-negotiable part of following the boating rules of the road.

Nighttime Navigation Lights Explained

Every vessel on the water at night must display a specific set of lights. The color and arrangement of these lights are your first and best clue to what's happening out there. The three main colors you’ll be working with are red, green, and white.

A standard powerboat underway will always have a green light on its starboard (right) side and a red light on its port (left) side. These sidelights are designed to be visible across an arc of 112.5 degrees each. You'll also see a white masthead light up front and a white sternlight facing backward.

If you see both a red and a green light at the same time, that boat is coming straight for you.

A simple way I've always remembered this is: "Red and green, a scary scene." It's a clear signal that you're looking at another boat head-on, and you need to prepare to alter your course to starboard for a safe port-to-port passing.

On the other hand, if you only see a green light, you're looking at the other boat's starboard side. In a crossing situation, this makes you the stand-on vessel. If you see only a red light, you're seeing its port side, which means you're the give-way vessel and must take action to avoid a collision.

Common Light Patterns You Must Know

Learning to identify different vessels at a glance is a game-changer. Here's a quick-reference table to help you recognize some common light configurations you'll see after dark.

Common Navigation Light Configurations at Night

| Light Combination You See | What It Means | Your Required Action |

|---|---|---|

| Red over Green | Sailing vessel under sail | If under power, you are likely the give-way vessel. If it's under sail, it has right-of-way. Give way. |

| One White light (all-round) | Vessel at anchor | It's stationary. Steer clear with plenty of room. |

| Two White masthead lights (vertical) | Vessel towing another boat | Stay clear. The towline may be hard to see. If you see three white lights, the tow is over 200 meters long. |

| Red over White | Vessel fishing (not trawling) | Remember: "Red over white, fishing at night." This boat has limited maneuverability. Give it a wide berth. |

| Green over White | Vessel trawling (fishing with nets) | Like other fishing vessels, its ability to move is restricted. Stay well clear of its nets and gear. |

These are the basics, but they'll cover most of what you encounter. For a more comprehensive look at what all the different signs and signals mean, our guide to boat navigation signs explained is a great next step.

Daytime Signals Using Shapes

During the day, when lights are hard to see, vessels use simple black geometric shapes to signal their status. These "day shapes" are hoisted high up on a mast so they can be seen from miles away.

- A single black ball means the vessel is at anchor.

- Two black balls in a vertical line mean the vessel is "not under command"—maybe it has a dead engine or steering failure.

- A ball, a diamond, and another ball (top to bottom) means the vessel has a restricted ability to maneuver, perhaps because it's dredging or laying cable.

By memorizing a few of these key shapes, you can understand a vessel's situation from a distance and make smart, safe decisions long before you get close.

Using Sound Signals and Navigating in Low Visibility

When fog, heavy rain, or the deep black of night rolls in, your eyes can quickly become unreliable. This is where the boating rules of the road shift from sight to sound. Your ears, guided by the language of sound signals from a horn or whistle, become your most critical tools for staying safe on the water.

Think of these sound signals as your boat's turn signals and hazard lights. They're a straightforward, effective way to broadcast your next move and make sure everyone nearby knows what you're doing. Skipping them is like driving down a highway with broken brake lights—you’re creating a ton of dangerous guesswork for everyone else.

Communicating Your Moves with Sound

Even on a crystal-clear day, seasoned boaters use sound signals to double-check their maneuvers. It adds an extra, crucial layer of safety on top of the standard right-of-way rules. The signals are simple, direct, and leave no room for misinterpretation about your boat's change in direction.

Here are the essential maneuvering signals every skipper needs to have memorized:

- One Short Blast: "I intend to leave you on my port (left) side." This almost always means you're turning your boat to starboard (right).

- Two Short Blasts: "I intend to leave you on my starboard (right) side." This tells other boaters you're altering your course to port (left).

- Three Short Blasts: A clear and simple message: "I am operating astern propulsion." In other words, your engine is in reverse.

- Five (or more) Short Blasts: This is the universal danger signal. Use it when you don't understand another boater's intentions or you believe they are about to cause a dangerous situation.

Using these signals makes your actions predictable. For example, if you're the stand-on vessel in a crossing situation and start your turn, a quick blast from your horn confirms to the other skipper that you've seen them and are maneuvering correctly. It removes all doubt.

Navigating in Restricted Visibility

When you can't see other vessels, you have to let them hear you. The rules require very specific sound patterns in fog or other poor-visibility conditions to turn your boat into an auditory beacon. These signals don't just say, "I'm here"—they tell other boaters what you're doing.

These are the most critical signals you'll use or hear in the fog:

- One Prolonged Blast (4-6 seconds) every two minutes: This is the sign of a power-driven vessel underway and making way (actually moving through the water).

- Two Prolonged Blasts every two minutes: This indicates a power-driven vessel that is underway but stopped (drifting, not making way through the water).

- One Prolonged Blast plus Two Short Blasts every two minutes: This is the signal for vessels that are restricted in their ability to maneuver, like sailing vessels, fishing boats, or towboats.

It’s a common and dangerous mistake to go quiet once you hear another boat’s signal nearby. That’s precisely when you need to keep signaling! Continuing your signals allows the other vessel to track your position and status, helping you both pass each other safely in the blind.

Knowing these auditory rules is every bit as important as understanding navigation lights and right-of-way. In fact, U.S. Coast Guard data repeatedly shows that a huge percentage of boating accidents involve operators who've had no formal safety instruction. Mastering sound signals is a core skill for avoiding collisions and proves that on the water, what you hear can be far more important than what you see.

Special Rules for Channels and Busy Waterways

Think of busy channels and designated fairways as the highways of the sea. Just like on land, these congested areas demand a much higher level of awareness and strict adherence to specific boating rules. Traffic is concentrated into tight spaces, which means there's virtually no room for error. This isn't just about courtesy; it's about understanding the very real physical limitations of other vessels.

Imagine you're at the helm of a massive container ship trying to navigate a dredged channel. That ship is like a freight train stuck on its tracks—it simply can't swerve or slam on the brakes to avoid a small boat that gets in its way. From the bridge, the blind spot directly in front of the bow can stretch for a quarter-mile or even more. If you're in a small boat crossing in front of them, the captain literally cannot see you.

Staying Clear in Narrow Channels

This is exactly why Rule 9 of the Navigation Rules is so important. The entire rule is built around respecting the maneuvering challenges of large vessels in confined waters. The language is crystal clear and leaves no room for interpretation.

The core idea is straightforward: if you are in a smaller boat, you absolutely must not get in the way of a large vessel that can only operate safely within the deep water of a narrow channel. Specifically, the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea state that vessels under 20 meters (about 65 feet), sailboats, and fishing boats must not impede the passage of these larger ships.

A common and dangerous mistake is assuming the usual "pecking order" applies everywhere. In a narrow channel, a sailboat or a fishing boat must give way to a large power-driven vessel that is constrained by its draft. Your job is to stay out of the main channel whenever you can.

Understanding Traffic Separation Schemes

In some of the world's busiest waterways, authorities set up Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS) to keep things orderly. These are essentially divided highways on the water. They have designated lanes for inbound and outbound traffic, all separated by a buffer zone.

If you find yourself needing to cross a TSS, the rule is to do so on a heading that is as close to a right angle (90 degrees) to the flow of traffic as you can manage. Picture crossing a multi-lane highway on foot—you wouldn't jog diagonally through traffic. You'd find the shortest, most direct path to get across safely.

When navigating these organized waterways, remember these key points:

- Follow the Lane: Always travel in the correct traffic lane, moving in the general direction of traffic for that lane.

- Keep Clear: Make sure to stay well clear of the separation line or zone between the lanes.

- Enter and Exit Carefully: Normally, you should join or leave a traffic lane at its designated endpoints. If you have to enter or leave from the side, do it at the smallest angle possible relative to the flow of traffic.

Following these special rules creates predictability and order in the most crowded marine environments. It’s the best way to protect both your own vessel and the massive commercial ships sharing these vital corridors.

Common Questions About Boating's Rules of the Road

Even when you feel you have a good handle on the basics, real-world situations can bring up tricky questions. Getting clear on the finer points of the boating rules of the road is what builds true confidence on the water, allowing you to react correctly and decisively.

Let's tackle some of the most frequent questions we hear from fellow boaters.

What's the Single Most Important Boating Rule?

If you had to boil it all down to one bedrock principle, it would have to be Rule 5: The Look-out Rule. This rule isn't just a suggestion; it’s a mandate. It requires every captain to maintain a constant, active watch using both sight and sound at all times.

This goes way beyond just glancing ahead. A proper lookout means maintaining a full 360-degree awareness of your environment to spot potential collision risks long before they become a close call. Think of it as your first and best line of defense—it’s the foundational habit that makes all the other right-of-way rules work.

Maintaining a proper lookout is not a passive activity. It is an active, continuous assessment of traffic, weather, and hazards that allows you to anticipate and react long before a situation becomes dangerous.

It’s no surprise that simple inattention is consistently listed among the top causes of boating accidents.

Do Kayaks and Paddleboards Have to Follow These Rules?

Yes, absolutely. The official Navigation Rules apply to every "vessel," and that legal definition includes everything from a supertanker right down to a canoe, kayak, or stand-up paddleboard.

While a paddler can turn on a dime, they still have a legal responsibility to know the rules. More importantly, they must take early and obvious action to stay well out of the way of larger boats that simply can't stop or maneuver as quickly. A little defensive paddling goes a long way.

Who Has the Right of Way: Powerboat or Sailboat?

In a typical open-water encounter, a sailboat under sail is the stand-on vessel, and the power-driven boat is the give-way vessel. This means the powerboat is responsible for making an early and significant course change to keep a safe distance.

But this isn't a blanket rule. There are a few key exceptions every boater needs to know:

- When Overtaking: The boat that is overtaking is always the give-way vessel. If a powerboat is passing a sailboat from behind, the powerboat must keep clear.

- When a Sailboat Uses Its Engine: The moment a sailboat turns on its motor (even if the sails are still up), it legally becomes a power-driven vessel and must follow the same rules as any other motorboat.

- Facing Less Maneuverable Vessels: A sailboat must always give way to any vessel with less ability to maneuver. This includes large ships in a channel, a commercial fishing boat with its nets out, or any boat that is not under command.

At Boating Articles, our goal is to give you the clear, practical knowledge needed to be a safe and confident boater. From deep-dive guides to unbiased product reviews, we're here to help you navigate every aspect of the boating life. Explore more at https://boating-articles.com.