When it comes to docking a boat safely, your mantra should be slow and steady. Always approach the dock at a shallow angle, using quick, deliberate bursts of power to stay in command. If there's one thing every seasoned skipper knows, it's that "slow is pro." Rushing is what causes mistakes. A controlled, deliberate approach isn't just safer—it makes the whole process feel effortless.

Conquering the Docking Challenge

Let's be honest: docking can feel like the final, high-stakes exam after a perfect day on the water. It's the moment when a small miscalculation can turn into a costly and very public mistake. My goal here is to help you swap that docking anxiety for pure, repeatable confidence.

The most important rule I can give you is to keep your speed way down. Forget about looking slick with a fast approach. Focus on calm, controlled movements. That’s how the pros do it.

Mastering the Core Principles

Every great captain I know has internalized a few core principles that make docking second nature. Once you get these down, you'll be well on your way to docking perfectly every single time.

Here's what you need to understand:

- Your Boat's Pivot Point: A boat doesn't turn like a car. It pivots on a central point, usually about one-third of the way back from the bow. This means any steering input will swing the stern much more dramatically than the bow. Keep that in mind.

- Brief Bursts of Power: Lay off the constant throttle. Instead, use short, quick shifts into and out of gear. These little "nudges" are all you need to gently guide the boat exactly where you want it.

- Momentum is Your Friend (and Foe): Even a boat moving at a crawl has momentum. You have to learn to anticipate it. Use that subtle forward glide to ease into the slip, rather than trying to power your way in.

Ultimately, docking comes down to solid preparation and knowing what's happening around you. It's not about luck; it's about having a process you can rely on.

Pro Tip: Never approach a dock any faster than you're willing to hit it. I've seen this simple piece of advice prevent countless bumps, scrapes, and much worse. It's the perfect reminder to take it slow.

With recreational boating more popular than ever, mastering this skill is essential. The global market for boat docks and lifts hit approximately US$1.1 billion in 2023 and is only expected to climb. If you're curious, you can read more about boat dock industry trends to see just how big this is getting. All that growth means one thing: a lot more people are learning how to dock a boat, and you can be one of the ones who does it right.

Getting Ready Before You Even Approach the Dock

I’ve seen it a thousand times: a boat comes in a little too hot, the skipper starts barking orders, and suddenly everyone on board is scrambling. A smooth, graceful docking isn't about some secret trick; it's about what you do before you even get close to the pier. Those few minutes of prep out in open water are what separate a chaotic landing from a calm, controlled one.

First things first, slow down. Way down. Take a moment to talk with your crew, even if it's just one other person. Figure out which side you'll be docking on and make sure everyone has a specific, simple job. Trying to shout instructions over the engine and wind at the last second is a surefire way to create stress and confusion.

Get Your Lines and Fenders Set

Long before you’re in the tight confines of the marina, get your defenses ready. This means getting your fenders and dock lines set up while you still have plenty of room to drift.

Fenders: You'll want at least three fenders hanging on the side you plan to dock on. Don't just sling them over the side. Take a second to adjust them so they protect the widest part of your hull, with the bottom of each fender sitting just above the waterline. This is what will save your gelcoat from an expensive crunch against a piling.

Dock Lines: Get your primary lines out of the locker and uncoil them. Lay them on the deck so they’re clear of any knots and ready to go. You’ll want a bow line, a stern line, and at least one spring line prepped. The absolute last thing you need is someone wrestling with a tangled mess of rope as the boat drifts away from the dock.

A rookie mistake I see all the time is keeping lines stowed until the boat is just feet from the cleat. Have them coiled and ready to toss. It eliminates a huge source of panic and makes learning how to dock a boat a much less stressful experience for everyone involved.

The Crew Briefing: Talk is Cheap, Hand Signals are Gold

Clear communication is everything, but it's not always easy. Between the rumble of the engine, the wind, and other marina noise, spoken words can get lost in the shuffle. This is where a simple set of hand signals can be a game-changer.

You don't need a complex system. Something simple works best:

- Thumbs Up: I'm good, or the line is on and secure.

- Pointing: That's the cleat I'm aiming for.

- "Stop" Hand: Hold up, we need to abort and circle back for another try.

- Circular Motion: I need more slack in the line.

Give one person the bow line and another the stern. Critically, make sure whoever is handling that first crucial line—which is often a midship spring line—knows their only job is to get that line around a cleat. That one line can stop all forward or backward motion, giving you the control to pivot the boat and leisurely tie off the rest. It's the simplest secret to a perfect landing.

Reading and Using Wind and Current

Wind and current are nature’s invisible hands on your hull. I've seen them turn a simple docking into a nerve-wracking ordeal for new and even seasoned boaters. The secret isn't to fight these forces, but to work with them. Before you even think about your approach, just take a moment to observe.

What are the flags on shore doing? How are other boats sitting at their moorings? Even watching a bit of floating seaweed can tell you everything you need to know about the current. These are your real-time indicators. You have to figure out which force—the wind or the current—is the dominant one on any given day. That’s the one you’ll build your entire strategy around.

Developing Your Approach Strategy

Here's the golden rule every good skipper lives by: approach into the dominant force. Think of it as a natural braking system. If the wind is pushing you toward the shore, you want to motor into it as you approach the dock. This gives you incredible control, allowing you to use small, deliberate bursts of power to ease the boat forward. The wind or current will naturally slow you down, preventing you from coming in too hot.

On the other hand, trying to dock with a strong tailwind or a following current is a recipe for disaster. It’s like trying to parallel park with someone pushing your car from behind—it rushes you, kills your ability to steer effectively, and raises the risk of a hard, damaging impact with the pier.

My Two Cents: I always tell people to keep the wind or current on the bow whenever possible. It gives you the best authority from your rudder and propeller. If you absolutely have to dock with a crosswind, you'll need to get clever and use it to execute a controlled drift into your slip.

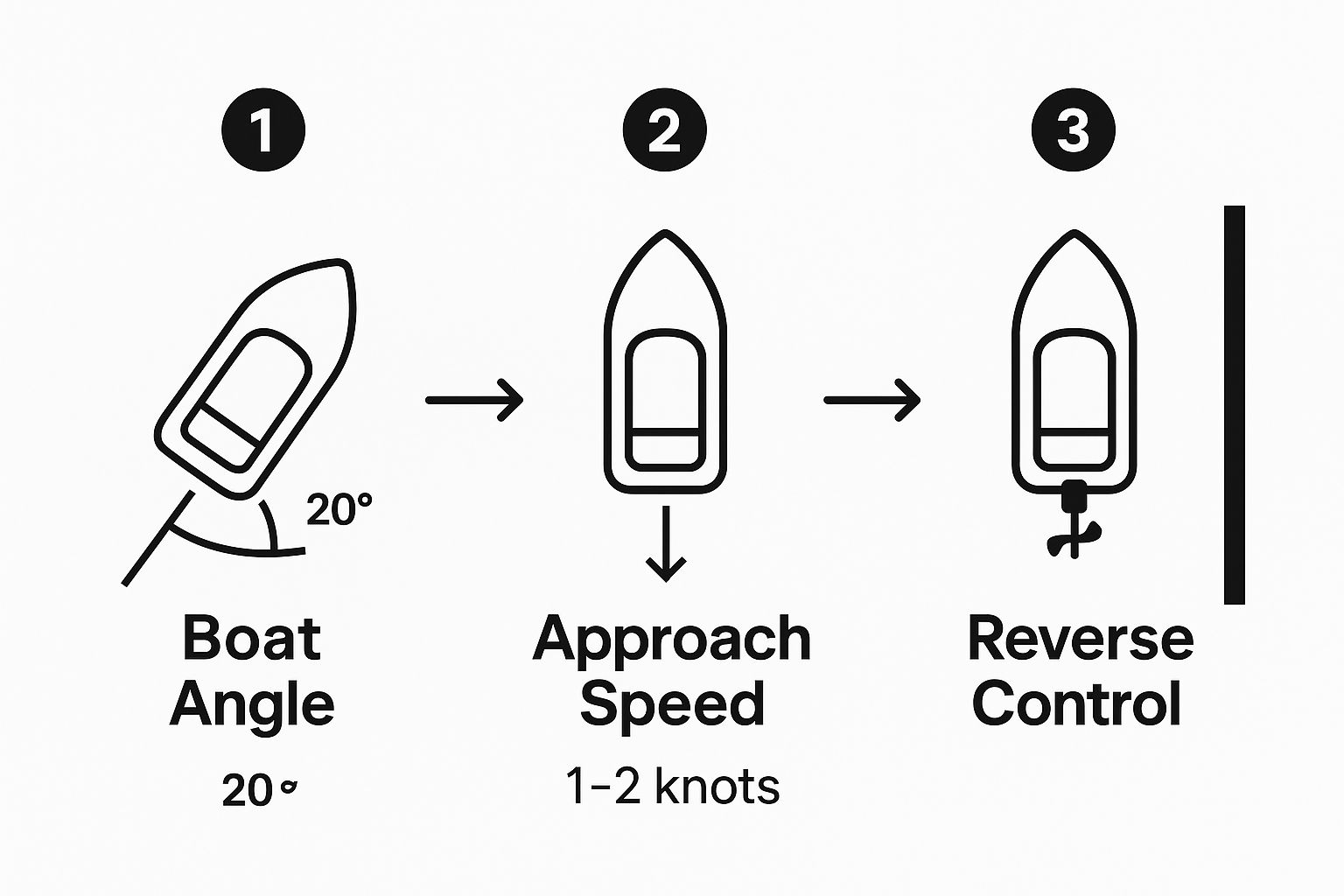

This image here gives you a great visual of that ideal, controlled approach.

As you can see, the key is a slow, shallow approach. You come in at a slight angle, and then a final nudge of reverse power pivots the stern in perfectly. It’s a beautiful thing when it all comes together.

To make it even clearer, I've put together a quick reference table for how to handle different conditions.

Docking Approach Strategy Based on Conditions

This table breaks down how you should adjust your approach based on what the wind and current are doing.

| Condition | Recommended Approach | Key Tactic |

|---|---|---|

| Wind/Current on the Bow | Approach directly into the force. | Use it as a natural brake for maximum control. |

| Wind/Current on the Stern | Find an alternate slip or wait. | Avoid if possible; it's the most difficult scenario. |

| Wind Pushing You Off-Dock | Approach at a steeper angle (~45 degrees). | Secure the bow line first, then spring the stern in. |

| Wind Pinning You On-Dock | Approach shallow and slow. | Use plenty of fenders to protect the hull. |

Having this mental checklist before you approach can take a lot of the guesswork out of the equation.

Managing Difficult Wind and Current

So, what do you do when the conditions are actively working against you? Every boater has been there. Here are a couple of common but tricky situations you'll definitely face.

-

Wind Pushing You Off the Dock: This is a classic crosswind problem. The trick is to approach at a much steeper angle than you normally would, maybe 45 degrees or so. The goal is to get your bow line to your crew on the dock as quickly as possible. Once that line is on a cleat, you can put the engine in slow forward and turn the wheel away from the dock. This technique is called "springing on a line," and it will use that bow line as a pivot to gently swing your stern right into place.

-

Wind Pinning You to the Dock: This makes for an easy arrival but can make leaving a real headache. Your main priority here is defense. Don't be shy with your fenders—they are your absolute best friends in this scenario and will prevent costly hull damage.

It's no surprise that the demand for quality docking facilities is on the rise. The boat dock market was valued at a whopping $1.76 billion in 2024 and shows no signs of slowing down. You can discover more insights about boat dock market trends if you're curious about the industry's growth. This just goes to show how many of us are out on the water, all facing the same docking challenges. Getting a handle on these forces is a skill that will serve you for a lifetime.

Bringing Her In: The Final Approach and Tying Up

This is it—the last few feet where all your planning comes together. The secret to a smooth, controlled finish is to think in gentle nudges, not constant power. You want to use short, deliberate shifts into and out of gear to gracefully guide the boat into place. This little trick is what separates a clean docking from the two most common mistakes I see: coming in way too hot or overcorrecting at the last second.

Your goal is to bring the boat to a soft stop, perfectly parallel to the pier. This lets your crew member step off safely—never jump—and get that first line secured. In most cases, that first line should be your midship spring line. Getting this on first is the key; it instantly stops the boat from drifting forward or back, buying you all the time in the world to get the other lines handled.

Getting That First Line on the Cleat

Think of that first spring line as your temporary anchor to the dock. The second your crew has it looped around a cleat, you’ve gained a massive amount of control. With that line set, you can use your engine and rudder to pivot the entire boat, swinging the bow or stern in or out as needed.

It works like this:

- Need to bring the stern in? Turn your wheel away from the dock and give a short burst of forward throttle. The spring line will act as a pivot point, pulling that stern right up against the bumpers.

- Need to pull the bow in? Turn the wheel toward the dock and give a quick bump of reverse. The same principle applies, and the bow will swing in while the spring line holds you fast.

The moment that first line is on, the pressure is off. You've essentially established control. This is the difference between a frantic scramble and a calm, professional docking maneuver. Now you can take a breath and secure the vessel properly.

This technique is a lifesaver whether you’re pulling up to a fixed concrete pier or a modern floating one. Floating docks are becoming incredibly common, especially where tides or water levels change. In fact, the market for these systems was valued at USD 0.29 billion back in 2024, which just goes to show how many boaters are using this adaptable tech. You can read more about the floating dock system market to see why they're so popular.

Securing Your Boat the Right Way

Once that spring line is on and the boat is sitting nicely parallel to the dock, it’s time to get your bow and stern lines tied off. Your crew on the dock should hand the lines back to someone on board to make the final adjustments and tie them to the boat's cleats. This is much safer and easier than having them try to pull against the boat's weight from the dock.

The go-to knot for this job is the cleat hitch. It’s incredibly strong, won’t slip, and—critically—is easy to untie even after it’s been under a heavy load. You just wrap the line around the base of the cleat, make a couple of figure-eights over the top, and finish with a locking half-hitch.

Properly tying off at the dock is just as crucial as knowing how to anchor correctly out on the water. For a refresher on that, feel free to https://boating-articles.com/2025/07/04/how-to-anchor-a-boat/.

With all your lines secured and adjusted for tide and conditions, you can finally shut down the engine. Job well done.

Handling Advanced Docking Scenarios

Once you've got the basic side-tie down cold, it's time to move on to the situations that can make even seasoned boaters sweat a little. These advanced maneuvers are where your feel for the boat really shines, turning what could be a stressful moment into a display of genuine skill. It’s all about applying what you know with a bit more finesse.

One of the most common challenges you'll face, especially in busy Mediterranean-style marinas, is the stern-to docking maneuver. This involves backing your boat into a narrow slip, often sandwiched between two others. It demands precision, but the reward is fantastic access from your swim platform right onto the dock.

Mastering the Art of Backing In

Successfully backing into a slip isn't about brute force. It's more like a controlled dance, guided by small, deliberate adjustments.

The real key is setting yourself up for success. Start your approach from a good distance out, pointing your stern directly at the slip's opening. This gives you a nice, long, straight runway to follow in reverse.

Use short, gentle pulses in and out of reverse gear to manage your speed. Keep in mind, your rudder is much less responsive in reverse, so your steering inputs should be small and patient. Let the boat's own momentum do the heavy lifting. If you find yourself getting crooked, don't try to wrestle it into place. The smarter move is almost always to pull forward, straighten out completely, and start your reverse approach again.

The number one mistake I see with stern-to docking is oversteering. A tiny turn of the wheel will create a big swing at the stern eventually. Be patient, think two steps ahead, and trust the boat's slow, predictable drift in reverse.

Working with Single-Screw Inboards and Prop Walk

If you're running a single-screw inboard boat, you need to become friends with a little quirk called prop walk. This is the tendency for the stern to "walk" sideways in the direction of the propeller's spin, an effect that’s most noticeable in reverse.

For a standard right-hand prop, your stern will want to walk to port (left) when you shift into reverse.

Don't fight it—use it! If you need to nudge your stern to port as you approach the dock, a quick shot of reverse will do the job for you, often without you even touching the wheel. Understanding your boat's prop walk is like having a secret, low-power stern thruster. It’s a non-negotiable skill for anyone handling this type of vessel.

Recovering When Things Go Wrong

Let's be real: nobody docks perfectly every single time. A sudden wind gust, a tricky current, or a dropped dock line can mess up even the most perfect plan. How you react is what matters.

- Coming in too hot? Don't panic. The second you realize you have too much speed, shift to neutral for a beat, then give it a firm burst of reverse. This will stop your forward momentum in its tracks.

- Wind pushing you around? Abort the mission. Seriously. It is always safer to circle back around for a second try than to fight a losing battle with a strong crosswind.

- Crew fumbles a line? Shouting doesn't help. Just calmly put the engine in gear, pull away from the dock, and circle around to set up another pass. Think of the first attempt as a practice run.

Having your boat properly outfitted with well-placed fenders is your best insurance against these little mishaps. To see how the right gear can prevent expensive mistakes, check out our guide on common docking mistakes and how fender bumpers can prevent damage.

Building these advanced skills is what gives you the confidence to know you can handle whatever the marina throws your way.

Common Boat Docking Questions Answered

Even when you've done everything right, docking can still throw a curveball. After years spent on the water and chatting with boaters at the dock, I’ve heard just about every "what if" scenario you can think of. Let’s tackle some of the most common questions to help you handle whatever the situation throws at you.

One I get all the time is, "What's the absolute best knot for my dock lines?" Hands down, the cleat hitch is king. It's incredibly strong, won't slip under load, and—crucially—it's easy to untie even after being strained by wind and current. If you master this one knot, you're set for almost any docking situation. For a deeper dive, you can see visuals on how to properly tie a boat to a dock.

How Many Fenders Do I Really Need?

Another area of confusion is fenders. How many is enough? Where do they go?

As a solid rule of thumb, always use a minimum of three fenders when tying up alongside a dock. This creates a safe buffer to protect your hull.

- Place one fender at your boat's widest point (the beam).

- Position another one forward of the beam.

- Hang the third one aft of the beam.

If you have a larger boat or you're docking in choppy water, don't hesitate to put out more. It's cheap insurance. Make sure you hang them so the bottom of the fender is just skimming the waterline. This gives you the best protection from both the dock edge and any pilings.

Think of fenders as the cheapest insurance policy you can buy for your boat's gelcoat. It's always better to have one too many than to be one short when a surprise gust pins you against a rough piling.

What if I Have to Dock in a Tight Spot?

We've all been there: a crowded marina with what looks like an impossibly tight slip. It’s nerve-wracking, but the key is patience and having an escape plan. Never try to muscle your boat into a space that feels too small or if your approach is just not working out.

The smartest move? Abort. Pull out, circle back around, and line up for another shot. A second or third attempt isn't a failure; it’s the mark of a cautious and skilled skipper.

Use small, deliberate bursts of power and let the boat’s own momentum do the heavy lifting. If you’re in a single-screw inboard, use that prop walk to your advantage to swing the stern in. Knowing you can always start over takes the pressure off, helping you stay calm and in full control.

Can I Leave My Boat at a Guest Dock Overnight?

Many marinas have guest or transient docks, but the rules can be wildly different from place to place. Some, like those you'll find on Lake George, are meant for restaurant patrons, while others are public access for short-term moorage. Before you tie up and walk away, always look for posted signs or check the marina's website.

Most public guest docks have clear limits on how long you can stay, which often changes based on your boat's size. For instance, a "trailerable" boat under 26 feet might get a 4-day limit, whereas a larger cruising vessel could be permitted to stay for up to 10 days. Expect to pay a fee, usually calculated per foot of boat length. Never assume an open spot is a free-for-all for an overnight stay without confirming the rules and paying up.

At Boating Articles, we're dedicated to helping you master every aspect of life on the water. From detailed how-to guides to unbiased product reviews, find all the expert advice you need at https://boating-articles.com.